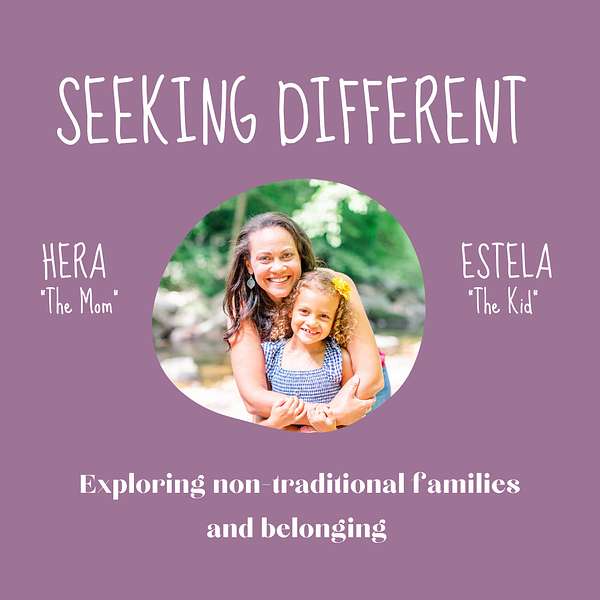

Seeking Different

Single Mother by Choice (former co-host of The Mocha SMC Podcast) Hera McLeod teams up with her precocious nine year old daughter Estela for the podcast "Seeking Different". The Mom and Kid duo explore what it looks like to navigate the world as a non-traditional family. They discuss hot topics such as donor sibling relationships, family travel, school choice, race relations, and navigating the playground.

Seeking Different

Season 2, Episode 8: The Man with 97 Biological Children (Part I) – Donor Dylan's Tale of Sperm Donation and Discovery

Ever wonder what it's like to walk into a sperm bank, answer some peculiar questions, donate, and then years later discover you have 97 biological children? That's exactly what happened to Donor Dylan, our guest in this riveting discussion. Dylan lets us into his journey of discovery, the shock of learning that he has a multitude of biological children, and the string of lies from the sperm bank that have shaped his life in unimaginable ways. We promise you a front row seat into the complex and often misunderstood world of sperm donation, as Dylan shares his quest to bring humanity into the business of creating humans.

Dylan doesn't shy away from the uncomfortable bits. He talks about the antiquated laws that hinder gay men from donating, and the uncanny questions thrown his way at the sperm bank. We also tackle the controversial issue of donor anonymity and the weighty responsibilities Dylan grapples with as he navigates ties with numerous biological children. Equally important, Dylan shares his heartwarming experience of being discovered by a group of mothers he donated to, and the profound connections he's formed with his donor-conceived families. Brace yourself for an enlightening and emotive journey that will challenge your understanding of sperm donation and its far-reaching implications.

Hi, I'm Hera the mom and I'm Estella the kid, and this is Seeking Different. There are times when everyone feels different or left out. As a non-traditional mom and kid family, we're sitting out to explore all the ways that families can be different. This is Seeking Different.

Speaker 2:Welcome to Seeking Different, so we're really excited to introduce a special guest to you all today. His name is Dylan, or aka Donor Dylan, on Instagram. I first saw Dylan's Instagram after the donor-conceived community shared one of his videos, and I really like how authentically he speaks about his experience as a donor and, in particular, some of the things he hopes that will change with the sperm industry.

Speaker 1:So let's get to it. Hi Dylan, thanks for coming to chat with us. I'm really excited to learn more about you and, in particular, what it's like to be a donor. Can you introduce yourself for our listeners?

Speaker 3:Yeah, thanks, estella. It's great to meet you and great to speak with you as well. Hera, really excited to chat with you all today. I'm Dylan, dylan Stone Miller. I was a teacher and in the nonprofit space in my 20s and then became a software engineer, working for cool startups using business to solve problems in the world. I was helping build apps that make people's lives easier.

Speaker 2:That's awesome. We're in tech as well, so very cool.

Speaker 3:I love it, yeah, so I recently quit my job, though, as a software engineer earlier this year to focus on my work with the United States Donor Conceived Council it's a nonprofit dedicated to the rights of donor conceived people here in the US and also to write a TV show about donor conception. Yeah, yeah, I decided to lean into my creative side and it's a lot more complicated than the simple software engineering very left brain stuff here. So, yeah, yeah, right, I hope to tell you know there are a lot of amazing and moving stories in the donor conception space and I'd like to help tell those stories in a fiction based on true events so more people understand what's going on in donor conception and lawmakers and the general public see the importance of honoring the needs of everyone involved in donor conception. In other words, my work right now is helping make the business of making humans a lot more human.

Speaker 2:Oh, I love that. Well, we really appreciate it, especially since we are a family that was created from donor sperm and my kids are donor conceived children, and so I must admit, when I first started this journey, I was very naive to how incredibly non-regulated the industry is, and I've come to find out in the last decade, since I've been a mom, that like wow, look, those things that I thought were just things weren't necessary things.

Speaker 1:How exactly did you end up with 97 biological kids?

Speaker 3:Yeah, that is a big question, estella. So I ended up with 97 biological children because the sperm bank told me that there would be a limit of 40 families that they would only use my genetic. 40 is still quite a lot, huh, I never thought that they would ever even approach 40. I thought, okay, that's gonna be. That's an astronomical number. There's no way that 40 would happen.

Speaker 3:None of my friends at the time who were also donating had reached anywhere close to that number, so it was my understanding that, okay, they'll reach some sort of limit and the rest will go to research. They told me that the genetic material would go to science. So I have no evidence that they won stuck to the limit of 40. In fact, right now it's at at least 62 families and there is no evidence that I have that they used any of my genetic material for research. So long story short, estella. They sort of lied to me, which I don't think was very nice, especially when I was trying to do something that helped people and not make so many that it made it harder for each of the families to to exist and navigate something that's very, very much more complex than it needs to be. Now.

Speaker 1:Yeah, that's not okay.

Speaker 3:Yeah, exactly, exactly. So one of the other things that they lied to me about is that they would be able to keep my identity a secret until the kids turned 18. They were not able to do that in this day and age, and in 2020, I was found by a group of about 40 mothers, all of whom had chose me as their donor.

Speaker 2:So how did that happen? Like how, exactly? How exactly were you found?

Speaker 3:Yeah, yeah. So yeah, gosh. It was really shocking. When they reached out, I was actually on the first day of a new job and 30 minutes into my new job I got a message from someone and it was a stranger at that time now a close friend who was thanking me for the gift of children, and I flipped over. It was on Instagram. I flipped over to her Instagram profile and saw pictures of a biological daughter for the first time and it moved me to tears. I had to stop myself from crying in the office, otherwise people would think I'm kind of strange for doing that right.

Speaker 3:But it turns out they, this family, was one of many families in a group, all of whom chose me as their donor and many of whom had actually found me online using clues from my donor profile. So they had things like my first name, my hometown, my parents' professions, and the woman who reached out to me had used all of those to find my father online actually, and she recognized his eyes. All she needed to do was search forensic psychology, atlanta, his profession and my home city and, after a little bit of scrolling, found him, recognized his eyes and, you know, heard she has two beautiful girls and they have the same eyes and I have those eyes too. So she, after some quick searching on his Facebook, she found me and followed me for a few months to see you know kind of who I was and what was going on in my life. And after a little while she recognized that I might be the safe person to reach out to and went ahead and did so and completely changed my life.

Speaker 2:So one of the things that is highly debated in the SMC community Single Mothers by Choice community is the concept of anonymity and the contracts that we sign. Because, like, as moms who use donors, like we sign a contract saying like we will not reach out before we will not reach out and when the children are 18, you know they can reach out and regardless of whether or not it's open ID or anonymous, like the bank will say, if the kids want to, they will try to broker the introductions. So I'm curious from your perspective, you know what? Would you tell moms that? Because I know many women that are like, oh, I know who the person is, Like I have found them in some way, but I am hesitant about reaching out. Like, how did it feel to you when it first happened? Just from the perspective of like, oh man, I was not expecting this yet.

Speaker 3:Yeah, yeah, I mean it was incredibly shocking. I will say I had a very unique set of circumstances at the time. I had just come off of a divorce and was isolated at the beginning of the pandemic so I was kind of all alone and feeling pretty sad. So getting a message like this was really beautiful to me and gave me an opportunity to show up for the families that wanted a connection and gave me an opportunity to multiply the love in my life. So I responded very positively towards this person reaching out. As shocking as it was, I didn't know how many families I was saying yes to, so at first it took me just a lot to understand and recognize this one family and to wrap my head around this little girl that I was seeing on my phone for the first time and that there was another little girl on the way and a whole family history that I had to get used to. And that was just one family. So when I agreed to connect with the group, I didn't know I was saying yes to 40 mothers representing about that same number of kids. So I got a little bit of a slow introduction to the group.

Speaker 3:I would recommend to folks who are reaching out to their donor to one do your homework on who the donor is. See if you, once you find them, see if you can see what's going on in their lives and if they seem like they're in a place where, oh, they have a family of their own, where they're raising kids and they have a job and all of these commitments and everything, then you should have the expectation that they aren't going to have as much time to dedicate to the donor families as I did. Because of my life circumstances, I was able to lean into this with all of me. So that's step one is do your homework.

Speaker 3:Step two, I would say, is to recognize that it's not necessarily your responsibility to connect your kids to your donor. It's the donor's responsibility to make a decision as to whether or not it is right and that they can show up for the kids in some small way, whatever way you determine. So before going into this and before guilting yourself over, I should be doing this for my child, or I should be. This is what a recipient parent should be doing. Recognize first what are your intentions in connecting. Is it just to get the medical records? Is it just to have the option to have the kids connect when they're 18? Audit yourself a little bit and then audit the person and when you are introducing yourself, start a little slow and see it just as an opportunity to express gratitude for the gift that they contributed to making your family. If you rush into it, then you are risking all of the families who could have a connection with them by potentially scaring this perfectly nice human being off.

Speaker 2:That would be my biggest concern. What sometimes people fail to realize is that there's a community of people that are impacted by your decisions, right, and I think that I personally feel like the kids should be a huge driver in all of that, because there might be some kids that don't want to.

Speaker 1:What is your relationship like with your bio kids?

Speaker 3:It's so special, estella. It's beautiful connecting with the kids and it's always super easy to get along with them because we tend to think and act a lot alike. I feel more grateful, as this experience evolves, for the memories we get to make. There are moments where I have to kind of just take a step back and see wow, we get to make these beautiful memories here together. So it's super fun. It's a lot of playing, it's a lot of hanging out, it's a lot of going to theme parks and silly things like that. Who knows what it'll look like in the future.

Speaker 2:So how do you connect with them now? I mean, there's 97 of them. Are you going on big family reunions or like, how does that work?

Speaker 3:Yeah, well, there's always discussion of a potential Disney World visit with all of us, or like a cruise or something like that, where it's a little easier to manage the kids and we don't have to feed everybody or clean up after everybody. But for now, what it looks like is I'm traveling around, largely around North America, though there are children in six countries, so Australia, uk, canada, israel and even one in China, as well as all over the US. So I am traveling around myself to visit them about once a year if possible, and then we'll do occasional FaceTimes as well, so we'll hop on the phone and do some video calls. I've had to get creative, though, with it, because there are so many. What I've been doing is recording myself reading, so I'll read some of my favorite kids' books from when I was a kid and sharing the recordings with the mothers online, and so the kids have been watching those and been getting a lot out of being able to hear my voice and see me when they express wanting to.

Speaker 3:So, yeah, it's a moving target. It's very. I do see it shifting in the coming years. I've been fortunate enough to chat with some donors who say well, high school, they'll have more autonomy to travel, at which point they can all come to one central location, like a lake house or something, and everybody can hang out once a year for a week, and that may be, that may be all the time that we all get together. And then, you know, in their 20s it looks a lot different because they start to have their own families and their own lives and things like that. So right now, in the golden years, if you will, I'm traveling around myself while I can, and I had had this remote job that has enabled my travel and things like that. So just enjoying making some memories in person and doing what I can to connect online while still managing my own life.

Speaker 2:Yeah, so take us back to like you as a 20-something walking into the bank, like, what is it like from the donor perspective? I've, you know, we've spoken to lots of nontraditional families, so we've heard about like different variations on the recipient side. But I'm curious, you know what was that experience? What was that experience like, and did you have a clear reason for doing it? How are you feeling back in your 20s when you did this?

Speaker 3:Yeah, I wanted to help families and science and saw an opportunity to make money rather easily while doing both of those things. So I really needed to pay for expenses in college and grad school and things like tuition and other things that come up when you're young. So I did what I thought was best and allowed my friend to refer me to this program. I already had a roommate who was donating so it was kind of normalized. People were already donating and getting a lot out of it and recognizing that we're helping families made it that much better. So I walk into the Sperm Bank and they say they start asking me questions like how tall are you and what's your health history like, and have you been to Africa in the last five years, and really strange questions that I had.

Speaker 2:So what is that a deal breaker if you've been to Africa the past five years.

Speaker 3:Yeah, there are still some weird laws. Yeah, I suppose there are some concerns with the people bringing certain diseases back from the continent, but it's a little strange that it's just sort of the entire continent as a whole and not maybe some more specific places that they might be worried about. But there are all sorts of antiquated laws and things like, for example, gay men can't donate, and so they were asking me questions about my sort of romantic life. Is that?

Speaker 2:a federal law? Or is that just like bank by bank?

Speaker 3:No, that's a federal law.

Speaker 2:That's so bananas. I mean it's like why you can't inherit it Right.

Speaker 3:And gay men are more likely to donate. So if they're worried about shortages of sperm, then they should redact that silly relic of a law from the AIDS epidemic in the 80s.

Speaker 2:That's probably also tied to the Africa thing too, right, because?

Speaker 3:there's probably a big bomb of that.

Speaker 2:Like oh, you went to Africa. That means you contracted HIV when you were there.

Speaker 3:Yeah, gosh, there's a zip code in Atlanta that has as high rates of HIV as some sub-Saharan African countries, so it's a little silly for us to be trying Anyways, and they can test for that stuff, so why would they not just run the test?

Speaker 2:Anyway, right, you can't just like you don't donate and then all of a sudden, like the next day, someone gets the sample, like you have to.

Speaker 3:It has to be four months. Yeah, yeah, exactly. So they start asking me all these really strange questions that I have to answer on the spot and I do, and they put you through a little bit of a. You know they'll do blood work and I was getting free healthcare from this place, so it wasn't just a financial incentive, there were some other incentives. You know, I thought I was helping people in science and I was getting free healthcare and the people really super friendly at the front desk.

Speaker 2:So my free healthcare is the when.

Speaker 3:Is that entail Like you get checkups or Physicals and blood work done, full STI panels and things like that. So, yeah, and so you know, every few months you're getting blood work done, every six months or so you're getting a physical. And you know I didn't have insurance at the time, so it was. I was like, okay, this is great, I'm able to sort of. In many ways it was really additive to my life and, again, with the people being so friendly at the front desk, as a young man you'd think, wow, this is a really wonderful gig. And, like all things that are too good to be true, it turns out yeah, they were lying to me and were exploiting me for profit, making $5,000 to $16,000 or more off the beach of my donations that they paid me $100 each.

Speaker 2:But that part is a little bit crazy. I know that there's some overhead that they have, but it just seems a little bit imbalanced in that I think I saw one bank was saying that with this one particular donor you had to buy all the vials, right, and it was something like $35,000. It could have been a situation where the person was just like I, only wanted to go to one family or something and they're still trying to make profit. But yeah, it just seems a lot. It seems like they're definitely out like fat rats.

Speaker 3:Yeah, yeah, I've seen that number too, the $35,000 number, and I even saw one that was $70,000 to be the sole family or a limit of five families and whatnot. So they're recognizing that people are taking issue with the size of the stippling pots, that they're creating and figuring into their business model, a way to make enough money that they can forgo over distributing sperm, like they did with me.

Speaker 1:Are you married and do you have children of your own?

Speaker 3:I am not married, Estella. I was raising a little boy who did not come from my biology, because family can look However we want family to look. I call him my soul son. He's very special to me. I still see him on Saturday it's when my ex-wife allows me to and so I don't have any biological children of my own. That would come with a lot of its own responsibilities as far as telling them that I was a donor and making sure that they know that they have biological siblings out in the world so that they can be safe when they become adults and start to go out into the world and don't accidentally run into their sibling without knowing it.

Speaker 2:So I love that you have the experience of raising a child that is not your biological son, because, I mean, it's interesting because there are so many families out there that are created with donor sperm, where they may have a spouse or someone in the house that is not their biological parent, but they're still a parent or a parental figure. It's great that you have that experience as well as being a donor.

Speaker 3:I think it gave me the empathy that I needed to enter into this wildly complex situation. I'm in direct contact for life with many, many parents now who are raising children of my biology. So if I were coming into this with no reference point for understanding what it's like to parent, then I think I would have just botched this situation horribly. But being able to say, oh no, I understand, if you all want to night out while I'm in town, then I'll take care of the kids, I'll babysit. I'm not stressed about aligning schedules and things like that. There's just so much that goes into parenting. I respect it so much that I'm able to show up in these families' lives without being a bullet in China shop.

Speaker 2:Thanks so much for joining us for part one of our conversation with Donor Dylan Tune. In next week for part two.

Speaker 1:Thank you so much for taking the time to listen to Seeking Different.

Speaker 2:If you like what you heard, share us with your family and friends.

Speaker 1:Tell us what you'd like to hear on future episodes and share your stories about belonging and family.

Speaker 2:You can connect with us on Instagram at Seeking Different.

Speaker 1:See you next time.